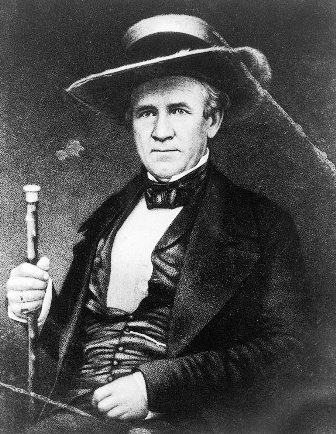

SAM HOUSTON

Signer of the Declaration of Independence – Commander-in-Chief of the Texas Army – President of the Republic – Member of Congress of the Republic – Senator in the United States Congress – Governor of Texas

His early life–Joins the United States Army–Wounded in the Battle of Horseshoe–Studies Law–Elected Member of Congress and Governor of Tennessee–Came to Texas in 1833–Delegate to Old Washington Convention–Appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Texas Army–Defeats Santa Anna at San Jacinto–Elected President of the Republic–Senator in the United Sates Congress–Governor of Texas–Death in 1863.

Sam Houston was born near Lexington, Rockbridge County, Virginia, March 2, 1793. His ancestors were of Scotch origin. They came to America about 1689 and settled in Pennsylvania. Robert Houston, Sam Houston’s grandfather, moved to Virginia and settled Rockbridge County. Here he reared a family and here Sam Houston was born. After the death of his father, his mother moved to Blount County, Tennessee. He was but a lad of thirteen summers when his mother changed her residence from Virginia to the rugged State of Tennessee. Here he came in contact with the Cherokee Indians, who lived near where his mother settled. He spent many leisure hours with them, joining them in their chase for game, which was in abundance at the time. In 1813, Mr. Houston enlisted in the United Sates army. The country was then at war with Great Britain. He was not in the army long before his peculiar talents for military life were recognized. He was soon promoted for gallantry in the battle with the Creek Indians. In a fierce conflict at To-ho-ne-ka, (Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River), Alabama, he received a painful wound from an arrow from an Indian bow. General Jackson ordered him to the rear, but he disregarded the order and joined his regiment in the thickest of the battle. As the battle raged he received another wound that disabled him and from this he did not recover for many months, and did not rejoin his regiment until a short time before peace was declared. He then served for a short time in the Adjutant General’s office at Nashville. In November 1819, he was assigned to extra duty as sub-agent among the Cherokee Indians, to carry out a treaty just ratified with the nation. During the winter of 1819-1820 he conducted a delegation of Cherokee Indians to Washington to present their claims to the Federal Government. Regarding Houston’s military career in the United States army, a memorandum from the war department shows that “Sam Houston entered the Seventh Infantry as a Sergeant; became ensign in the Thirty-ninth Infantry, July 29, 1813; was severely wounded in the battle of Horse-shoe Bend under Major-General Jackson, March 27th; made Third Lieutenant December1813; promoted to Second Lieutenant May, 1814; retained May 15th in First Infantry; became First Lieutenant March 1, 1818; resigned May 17, 1818.” Soon after resigning from the army Mr. Houston entered the law office of Mr. James Trimble, an eminent lawyer at Nashville, for the purpose of studying law. He was soon admitted to the bar and at once became a successful advocate, locating in Lebanon. He was soon elected District Attorney. This made it necessary for him to reside in Nashville. His resident in Lebanon was so pleasant that he left it with regrets. When about to move to Nashville he delivered a public address to the citizens of Lebanon in which he expressed regrets that it became necessary for him to leave them. In his address he said: “The time has come when I must bid you farewell. Although duty calls me away, yet I must confess it is with feelings of sincere regret that I leave you. I shall ever remember with emotions of gratitude the kindness which I have received at your hands. I came among you poor and a stranger and you extended the hand of welcome, and received me kindly. I was naked and ye clothed me–I was hungry and you fed me–I was athirst and ye gave me drink.” “Mr. Houston’s address” said I. V. Drake, in a letter to his biographer, Dr. William Carey Crane, “was delivered in so pathetic a style that its effect was to cause many to shed tears.” In 1820 Mr. Houston was appointed Adjutant-General of the State, with the rank of Colonel. In 1821 he was elected Major-General by the field officers of the division that composed two-thirds of the State.

Sam Houston In 1822 he was elected a member of the eighteenth United States Congress and was re-elected to the Nineteenth Congress, thus serving in that body from March 4th, 1823 to March 3rd, 1827. In the election of 1826 he was elected Governor of Tennessee, but resigned after a few months service and went to the Territory of Arkansas and sought his old friend, Chief Oelooteka, of the Cherokee Indians. He was welcomed by the old Chief and treated as a son, –a voluntary exile from civilization. Here he remained until December 1, 1832, when he set out for Texas, having been appointed by President Jackson on a secret mission among the Indian tribes of Texas. He crossed Red River early in 1833 and went direct to Nacogdoches. After a short rest at Nacogdoches, he continued his journey to San Antonio and San Felipe. On February 13, 1833, he forwarded from Nacogdoches a report of his journey in Texas to President Jackson. While in Nacogdoches the residents of that place urged him to become a citizen of Texas, and to permit them to elect him a delegate to the convention which had been called to meet at San Felipe, April 1st. To this he consented and his appearance at San Felipe, as a delegate to this convention, was his introduction to the leaders of affairs in Texas. This convention drafted a constitution for the State of Texas separate from that of Coahuila. Mr. Houston was appointed chairman of the committee which wrote the proposed constitution. From this time on Mr. Houston was a central figure in Texas affairs. Mr. Houston made a tremendous impression on the delegates to this convention who saw in him an able ally and a leader of power, and many were the expressions of appreciation that he had cast his fortunes with the struggling colonists. Mr. Houston continued to reside in Nacogdoches and in the fall of 1835 he was elected by the committee of Safety of Nacogdoches and San Augustine, Commander-in-Chief of the military forces of the municipalities of Nacogdoches and San Augustine, which embraced practically all of the state east of the Trinity river. The proclamation of the Committee of Safety of San Augustine announcing Mr.Houston’s election was as follows: Committee Room, San Augustine, Oct 6, 1835 Whereas, in the present emergency, organization and energy of action are necessary, and whereas we see the great necessity of a commander-in-chief of this department, for the purpose of issuing orders, raising troops, etc. and being well satisfied of the fitness, capacity and fidelity of General Samuel Houston for such a station: be it therefore Resolved: that we, with the concurrence of the committee of safety for the municipality of Nacogdoches, do hereby appoint the said Samuel Houston, general and commander-in-chief of the forces of this department, vesting him with the full powers to raise troops, organize the forces, and do all things appertaining to such office; and be it further Resolved: that the powers of said commander continue in force till the General Consultation of Texas shall make further provisions; and be it further Resolved: that the said Houston be required to issue proclamations, and call for recruits, and to do all things in his power to sustain the Constitution of 1824. Philip Sublett, Chairman A. G. Kellog, Secretary. It will be noted that it was made the duty of the Commander-in-Chief to issue proclamations and to call for recruits and to “do all things in his power to sustain the principles of the Constitution of 1824,” and that the powers of said Commander-in-Chief “continue in force until the General Consultation of Texas shall make further provisions.” On the second day following his appointment as Commander-in-Chief, October 8, 1835, Mr. Houston issued an order which read as follows:

Headquarters, Texas Department of Nacogdoches October 8, 1835 The time has arrived when the revolutions in the interior of Mexico have resulted in the creation of a dictator and Texas is compelled to assume an attitude defensive of her rights, and the lives and property of her citizens. “Our oaths and pledges to the constitution have been preserved inviolate. Our hopes of promised benefits have been deferred. Our constitutions have been declared at an end, while all that is sacred is menaced by arbitrary power! The priesthood and the army are to mete out the measure of our wretchedness. War is our only alternative! War in defense of our rights must be our motto! “Volunteers are invited to our standard. Liberal bounties of land will be given to all who join our ranks with a good rifle and one hundred rounds of ammunition. The troops of the department will forthwith organize, under the direction of the Committee of Vigilance and Safety, with companies of fifty men each, who will elect their officers, and when organized they will report to the headquarters of the army, unless special orders are given for their destination. “The morning of our glory is dawning upon us. The work of liberty has begun. Our actions are to become a part of the history of mankind. Patriotic millions will sympathize in our struggles, while nations will admire our achievements. We must be united–subordinate to the laws and authorities which we avow, and freedom will not withhold the seal of her approbation. Rally around the standard of the constitution, entrench your rights with noble resolution, and defend them with heroic manliness. Let your valor proclaim to the world that liberty is your birthright. We cannot be conquered by all the arts of anarchy and despotism combined. In heaven and valorous hearts we repose our confidence. “Our only ambition is the attainment of national liberty–the freedom of religious opinion and just laws. To acquire these blessings, we solemnly pledge our person, our property and our lives. “Union and courage can achieve anything, while reason combined with intelligence can regulate all things necessary to human happiness.

Sam Houston General-in-Chief of Department.”

Sam Houston's Autograph

This appeal to the patriotism of the men of eastern Texas was received by them with a solemnity that greatly touched their pride and ambitions and aroused them to action and soon the whole country was afire with military ardor. But events of tremendous gravity came fast upon the scene and changed the plans inaugurated at the instance of the Committees of Vigilance and Safety of Nacogdoches and San Augustine. A consultation of all the people of Texas had been called to meet at San Felipe in November and General Houston had been elected a delegate to this convention and those in authority in eastern Texas urged him to attend. He did so and became a conspicuous leader in its deliberations. When a proposition was submitted to at once proclaim Texas absolutely free of Mexico, he led the opposition to the plan. He expressed his unwillingness to so abruptly abandon the principles of the Constitution of 1824 and favored the organization of a government pledged to its principles. He did not feel that the time had arrived when the colonists could afford to renounce their former adherence to the Constitution of 1824. The proposition was defeated after an acrimonious debate and in its stead the Consultation established a provisional Government and elected a Governor, a Lieutenant-Governor, a legislative Council and Commander-in-Chief of the army. Henry Smith was chosen Governor, J. W. Robinson, Lieutenant-Governor; Sam Houston, Commander-in-Chief of the army. The Legislative Council was composed of one member from each municipality of the state. The convention differed very materially from the conventions of 1832 and 1833, in that the delegates to this convention were in open rebellion against Santa Anna, upon whom the conventions of 1832 and 1833 had depended for redress against the despotic rule of Bustamante. The provisional government began functioning immediately after the adjournment of the convention, November 14th. Governor Smith sent his first message to the Council November 15th. Prior to the election of General Houston as Commander-in-Chief of the Texas armies, the army was under the command of General Edward Burleson, a most worthy and capable military leader. But a state of war existed and the members of the Consultation recognized in General Houston a military chieftain of superior military genius. General Burleson had shown his gallantry and loyalty in many conflicts with the enemy and was held in the highest esteem by the army and the people. But Houston’s military record and account of his prowess had preceded him to Texas and all eyes turned to him as better equipped by training and experience to lead in the war which all felt sure would soon be waging in all its fury. Early in 1836 military events transpired which greatly embarrassed Governor Smith and General Houston and threatened the life of the provisional government. The General Council had so conducted itself as to lose the confidence of Governor Smith and bring on an open breach between that body and the executive. There were doubtless men in that body opposed to the military programme being worked out by the Commander-in-Chief of the army, and they adopted a programme which violated the mandates of the organic law and conflicted with the authority of the Commander-in-Chief. These men met as a Council from day to day, without a quorum, and authorized a military programme calculated to supersede General Houston. In this they were unsuccessful and disaster came to all their efforts, and the unfortunate destruction of many lives. When Governor Smith learned that troops were being mobilized in Southwestern Texas for the purpose of attacking Matamoras, and of their refusal to obey orders emanating from the legal authorities of the government, he ordered General Houston to proceed to Refugio. He obeyed these instructions. He reached Goliad about the middle of January and made known to the troops there the object of his visit, and enjoined obedience to his authority. Colonel Grant was just on the eve of marching from Goliad to Refugio where a junction of the troops of Grant and Fannin were to be made. Grant and his troops refused obedience to the orders of Governor Smith, submitted to them by General Houston. General Houston could not understand this extraordinary conduct as he was ignorant of what the Council had done. But in the face of the conduct of Grant and his troops General Houston marched with him to Refugio. “Unable,” says Crane, “to influence the leaders by regular authority or by friendly remonstrance and, unwilling to invite sedition among the troops, reluctant to bow to the command of any other officer, accompanied by a few of his staff, General Houston set out at night from Refugio to return to San Felipe.” Before reaching San Felipe the alarming condition of the country was disclosed to him. Published letters of Colonel Fannin, indicating his disregard of the authority of Governor Smith and the Commander-in-Chief of the army met his eyes. He realized more fully than ever before that quick action was necessary to forestall the evil about to be done, or confusion would follow and all would be lost.

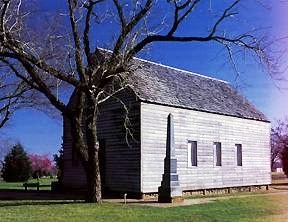

Independence Hall at Washington-on-the-Brazos where Sam Houston Signed the Declaration of Independence from Mexico A convention had been called to meet at Old Washington, March 1st. The people of Refugio had elected him a delegate to this convention which trust he accepted. On reaching San Felipe, he filed with Governor Smith his official report of his visit to Refugio, and then in obedience to instructions from Governor Smith proceeded to the Cherokee Nation to form a treaty with them and other nations. The other commissioners were John Cameron and Colonel Forbes. Major George Hockley accompanied General Houston to the Cherokee Nation and there Mr. Houston and Mr. Forbes met the Indians in Council and accomplished the objective of their mission. General Houston then returned to San Felipe and secured a furlough from the army to enable him to sit as a delegate in the convention which met at Old Washington March 1st. This convention adopted a Declaration of Independence from Mexico, March 2, and he was a signer of that instrument. A constitution was also adopted and birth given to the Republic of Texas. On March 6th, a message was received from Colonel W. B. Travis, Commander of the forces at the Alamo, of the most thrilling character. It advised that the Alamo was being besieged by Santa Anna’s army of several thousand troops. The reading of this letter created great excitement among the delegates who had assembled in the convention hall to hear its contents. “After it was read,” said one of the members of the convention, “painful silence prevailed for a brief period. Despair was pictured in the faces of the bravest and best. Just what to do was a question that puzzled us all. But that immediate action was imperative and plainly our duty, was the feeling of all. Finally, amidst momentary confusion delegate Robert Potter moved “that the convention do immediately adjourn and march to the relief of the Alamo.” A deathlike stillness followed. Sam Houston rose from his seat. All eyes were fastened on his stately form. For a moment he stood like marble and casting his eyes over the assembled delegates, he addressed the chair in opposition to Mr. Potter’s motion. It was a moment fraught with tremendous consequence. He told the convention that the fate of Texas hung in the acts of the convention; that it would be worse than madness for the convention to adjourn before completing it work; that a Declaration of Independence without an organization to sustain it would make it void. He urged the convention to quietly pursue its deliberations and complete its labors. Houston spoke with great eloquence and fervor and assured the convention that he would start for Gonzales where he would collect the little army there and go to the rescue of the defenders of the Alamo, guaranteeing them that no Mexican army would molest them while performing the labor expected of them by the people who sent them to Old Washington. At the close of his address Mr. Houston walked out of the convention. Tumultuous applause followed.” History tells us that in less than an hour Houston was on his way to Gonzales accompanied by a few brave companions. It appears that Travis had advised that as long as the Alamo held out against Santa Anna’s horde, signal guns would be fired each day at sunrise. Late at night on the first day Mr. Houston struck camp near enough to hear the signal gun. At sunrise on the following day he put his ears to ground in an effort to hear the distant signal, but alas! no sound was heard. The Alamo had fallen and there was none left of its brave defenders to fire the signal gun. Houston hastened on to Gonzales, weighted with forebodings that Travis and his brave band had fallen victims to Mexican tyranny. Mr. Houston arrived at Gonzales March 10th. Here he found a small body of men without discipline, unorganized and without arms, and poorly clad. They were soon assembled by General Houston, and placed under military discipline. Soon thereafter information reached Gonzales, that the Alamo had fallen the very day that the convention had received Travis’ appeal. Immediately, on being assured of the fall of the Alamo, General Houston sent a second express to Fannin at Goliad, advising of the fall of the Alamo and instructing him to abandon that Fort and fall back to Victoria, and the Guadalupe. He felt that the fate of Texas depended on the union of all the forces in the field. Fannin failed to obey General Houston’s orders promptly, assigning as a reason therefore, that a portion of his troops were attempting to rescue some families from Refugio and he was waiting their return. This delay was fatal to Fannin and his troops. When he left Goliad, he found himself surrounded by the enemy who attacked him in the open prairie, a short distance out of Goliad and, after a fierce conflict in which he had several of his men killed, and himself wounded, his whole command was betrayed into surrendering, and later all massacred. When the news of Fannin’s fate reached Houston’s little army a fearful panic took place, but Houston was not dismayed. He mingled with his brave little band and inspired them with renewed confidence, and began preparations to fall back to the Brazos. Before leaving Gonzales, however, he organized his forces. A regiment was formed with Edward Burleson, for Colonel, Sidney Sherman and Alexander Somerville Lieutenant-Colonel, respectively. General Houston, reached San Felipe, the second day of his march. On March 30th he reached the Brazos opposite Groce’s. He moved his army on an island of the Brazos and remained there until April 11th. He constructed a narrow bridge to the western bank to enable his scouts to pass over that they might keep an eye on the maneuvers of the Mexicans. He left a small guard at San Felipe. When Santa Anna approached San Felipe the little company of Texans crossed to the east side of the Brazos and built a crude fortification of timbers. When the Mexicans discovered them they opened their artillery on them. When General Houston learned that Santa Anna was crossing the Brazos with his troops, he dispatched orders to his scattered troops to join him on his march to Harrisburg. General Thomas J. Rusk, Secretary of War in President Burnet’s Cabinet, joined him about this time. The march to Harrisburg was beset with many difficulties. Heavy rains made the roads almost impassible and the baggage wagons had to be unloaded many times to enable them to proceed. There was not a tent in the army and the men slept on the cool and damp ground with the canopy of Heaven as their covering. The hardships they endured on this march have few parallels in modern history. The fourth day's march carried them to the east side of Buffalo Bayou within two miles of Harrisburg. Here Deaf Smith and Henry Karnes crossed the Bayou in search of information of Santa Anna’s army. They soon returned with two Mexican Couriers bearing dispatches from Filisola to Santa Anna. This was the first positive information that Houston had secured that Santa Anna was personally in command of the Mexican troops. Orders were at once given to cross to the south side of the Bayou. A small boat was used in crossing the men and baggage. The horses swam across.

Before crossing the Bayou, Houston let it be known that he was in search of Santa Anna, and a battle was to be fought as soon as he was located. As soon as the army had crossed the Bayou the companies were formed into line and General Houston rode upon his horse and addressed them. He told them that they must prepare for battle; that the enemy was near and whenever and wherever he was found he proposed to give battle. He gave then as the battle cry “Remember the Alamo.” Instantly the words were shouted out by every man present. General Houston feelingly referred to the cruelties of Santa Anna’s army; of the slaughter of Travis, of Crockett, of Bowie of Fannin, of Ward, of King and their companions; he told them the opportunity for revenge was near; that Santa Anna and his army were close at hand; that battle was inevitable and victory was sure. General Rusk followed with a strong appeal to the army to act well their part in the battle soon to take place. He closed his address with these words: “They are better equipped than we and their numbers are greater, but God and Right are with us and will give us the victory.” These addresses inspired every man of the little army and they waited only the orders to march. The order was soon given and the little band fell into line without the beat of a drum or the floating of banners. They were determined to conquer or die, and as they marched towards Santa Anna’s troops few words were spoken. Their minds and hearts were fixed on home, their families–their country. Reaching the point a few miles from where the supreme struggle was to be made, the army was halted. The weary men took shelter under the cover of a grove and laying down on their rifles, slept. General Houston rose at daybreak. Pickets were advanced from every direction and scouts were sent out. The scouts soon returned with information that Santa Anna with his army was near. Fires were built preparatory to the cooking of the beeves previously dressed. Before much progress with the cooking had been made, the scouts reported that Santa Anna was marching up from New Washington (Morgan’s Point) to cross the Bayou at Lynchburg. Houston determined to prevent this, and he gave orders to march down the bayou. The men abandoned their cooking and prepared to march. When they reached the ferry at the junction of Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto River, they learned that Santa Anna had not effected a crossing. The Texans took possession of the boats Santa Anna had had constructed and moved them opposite their camp. In a beautiful grove semi-circular in form on the margin of a prairie, Houston posted his army. His force was concealed by the timber and he planted his artillery on the brow of the timber. The Texans were ready for battle, but as Santa Anna’s army had not yet arrived, they lighted their fires to complete the cooking which they had shortly abandoned. The fires had scarcely been lighted when scouts rushed into camp announcing that the Mexicans were in sight. Santa Anna’s bugler sounded a charge. Santa Anna thought that he had surprised the Texans, but instead, he was surprised by the discharge of the Texan’s artillery, and the Mexicans were driven back in confusion. This occurred about 10 o’clock on April 20th. The skirmish concluded with the retirement of Santa Anna and his army to a swell in the prairie with timber and water in the rear, where he commenced the construction of breastworks. General Houston expressed satisfaction over the result of the engagement and said to one of his officers that he felt certain that by protracting the engagement that he would have defeated Santa Anna’s army, but it would have been attended with heavy losses of his men. “While tomorrow,” he said, “ I will conquer, slaughter and put to flight the entire Mexican army and it shall not cost us a dozen of our brave men.” The Texan army retired to their camp and refreshed themselves for the first time in two days. “The enemy” said General Houston in his official report, “in the meantime extended the right flanks of their infantry, so as to occupy the extreme point of a skirt of timber on the bank of Buffalo Bayou, and secured their left by a fortification about five feet high, constructed of pack and baggage, leaving an opening in the center of their breastworks, in which their artillery was placed, the cavalry upon their left wing.”

San Jacinto Monument Marking the Site of the Battle of San Jacinto. Photo courtesy of David Melasky

The Opportune Moment The opportune moment long hoped for by General Houston, had almost arrived. As his little army faced the Mexican army on the afternoon of the 20th, they were eager to begin the conflict, but General Houston had not thoroughly worked out his plan of attack, and the opportune moment had not arrived. But on that fateful April 21st, he summoned for consultation his officers, and laying his plans before them he bade them prepare for battle. The opportune moment had arrived. At three o’clock in the afternoon of April 21, 1836, the little Texas army was drawn up in battle array waiting for the order to charge. The Mexican army was concealed behind the breastworks, feeling secure and looking down with contempt upon the little Texan army. Santa Anna quietly rested in his tent under the delusion that the Texans would never attack him. His army had been reinforced by the arrival of about 500 well trained men, under General Cos, and Santa Anna and his troops were in high spirits. They were gloating over the slaughter of the defenders of the Alamo and the brave men under Fannin and Ward and King, and were waiting for the opportunity to butcher the only remaining defenders of the Texas Republic. They imagined that their task was an easy one and Santa Anna’s troops grew impatient because of delay. But they knew little of the Texans' spirit. They imagined that the slaughter at the Alamo, at Goliad, at Regugio, at San Patricio had sent terror to the Texan's hearts. But this was a fatal delusion. These heinous crimes only aroused the Texans' determination to seek restitution and when the order to charge was given they rushed into the face of the Mexican cannon with an impetuosity unparalled in modern warfare. The conflict lasted only about seventeen minutes. Santa Anna’s army of trained veterans in war were either put to the sword or routed, and Santa Anna, the self-styled “Napoleon of the West” fled a fallen hero to be captured the following day while hiding in the brambles. The war cry “Remember the Alamo! Remember the Alamo and Goliad” was shouted out with the order to charge by General Houston. The effect was instantaneous and aroused within the hearts of every Texan the determination to win or die. The shout of the Texans rent the air and drove terror to the Mexican invaders. As the charge was being made in all its fury, Deaf Smith rushed along the lines swinging an axe over his head and exclaimed in a stentorian voice: “I have destroyed Vince’s bridge–fight for your lives and Remember the Alamo!” At this moment, the Texans in solid phalanx rushed forward with relentless fury upon the breastworks of the Mexicans. At the head of the center column rode General Houston, into the face of the foe. The Mexican army was drawn up in perfect order. The Texans rushed on without firing a single shot, but as they approached the breastworks, the Mexican line flashed with a storm of bullets, but the God of war was with the Texans and the Mexican bullets flew over their heads. The Texans pressed forward in spite of the fact that their Commander had been badly wounded. Each man reserved his fire until he could choose some particular Mexican and before the Mexicans could reload, discharged his rifle into the very heart of the Mexicans. The Texans were without bayonets and converted their rifles into war clubs. A desperate hand to hand struggle took place all along the breastworks. When the Texans had, by smashing the skulls of the Mexicans, broken off their rifles at the breach, they flung the remnants at the terrified Mexicans and drawing their pistols continued the slaughter. When their pistols had been emptied they threw them at the heads of the terrified Mexicans and drew their bowie knives and carved their way through dense masses of human flesh. The Mexicans fought bravely, but vengeance which fired the Texans’ breasts was fierce and relentless. They were fighting for their homes, their families, their dead kindred and the undying rights of civil and religious liberty. They battled as none but men free-born and determined to die free can ever fight. When the Mexicans realized that the onslaught of the Texans could not be resisted they fled in dismay to be stabbed in the back. Many fell to their knees and cried out in pleading accent; “Me no Alamo! Me no Alamo!” No claim for mercy occurred to them but to disclaim participation in that brutal affair. But the Texans heeded not their appeal for mercy, remembering that no mercy had been shown their friends and companions by this same merciless band of invaders in their march from the Rio Grande to the San Jacinto. It is impossible for the language to describe the scene of the conflict. Even those who participated were unable to adequately picture it. Each was so intent on performing the task assigned to him that he gave little heed to the happenings around him. Few battles of the world have been more decisive and tremendous in their influence over civilization than the Battle of San Jacinto. It changed the map of the North American continent and opened the way for the United States to extend its boundaries to the Rio Grande on the Southwest and to the Pacific Ocean on the West. It sealed the destiny of the Texas Republic, confirmed the Declaration of Independence, drove from the country east of the Rio Grande an invading host and established liberty where tyranny sought to enthrone itself. Very soon after this victory at San Jacinto, General Houston repaired to New Orleans for surgical care. While in New Orleans the question of electing a President of the young Republic became a live issue and all eyes turned to General Houston, the hero of San Jacinto. In the election which followed he was chosen the first President of the Republic of Texas. The first Congress of the Republic of Texas organized at Columbia, October 3, 1836. Houston was inaugurated as president October 22. He served one term–two years only–because of a provision in the Constitution which read as follows: “The first President elected by the people shall hold office for the term of two years and shall be ineligible during the next term.” When Mr. Houston took the reins of government as President, he found an empty treasury and the country without credit. An army was in the field without means of support. A serious situation confronted him. He could not disband the army without paying the men off, so he concluded to reduce the army by issuing furloughs. He announced trade and commerce relations between Mexico and Texas. Trade sprang up rapidly. Everybody was for peace. His administration was successful and profitable to the country. After the expiration of Mr. Lamar’s term as second President, Mr. Houston succeeded him.

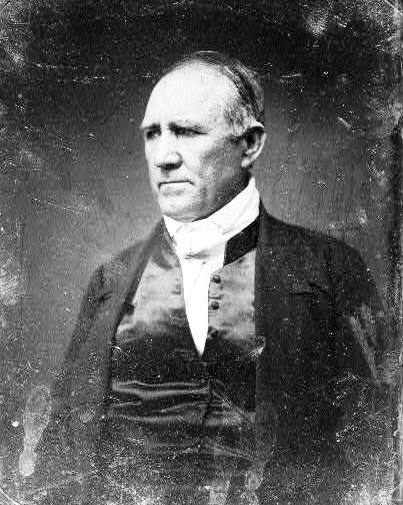

Sam Houston After annexation in 1845, the First Legislature of Texas elected him to the Senate in the United States Congress and he served in that body from February 21, 1846 to March 3, 1859. In 1858 he was elected Governor of Texas and took the oath of office the following January, 1859. He was deposed March 18, 1861, because he refused to take the oath required of him by the Legislature and the Secession Convention. He died in Huntsville, July 26, 1863. When the Legislature met in November following his death, strong resolutions of regrets were passed by that body.

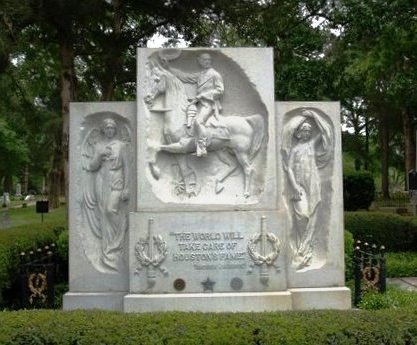

Sam Houston's Grave in Huntsville, Texas The inscription reads: "The World Will Take Care of Houston's Fame" Andrew Jackson

Text from The Men Who Made Texas Free, Sam Houston Dixon, 1924, Texas Historical Publishing Company, Houston, pp. 155-171.

"The World Will Take Care of Houston's Fame." Andrew Jackson "Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed." Neil Armstrong |